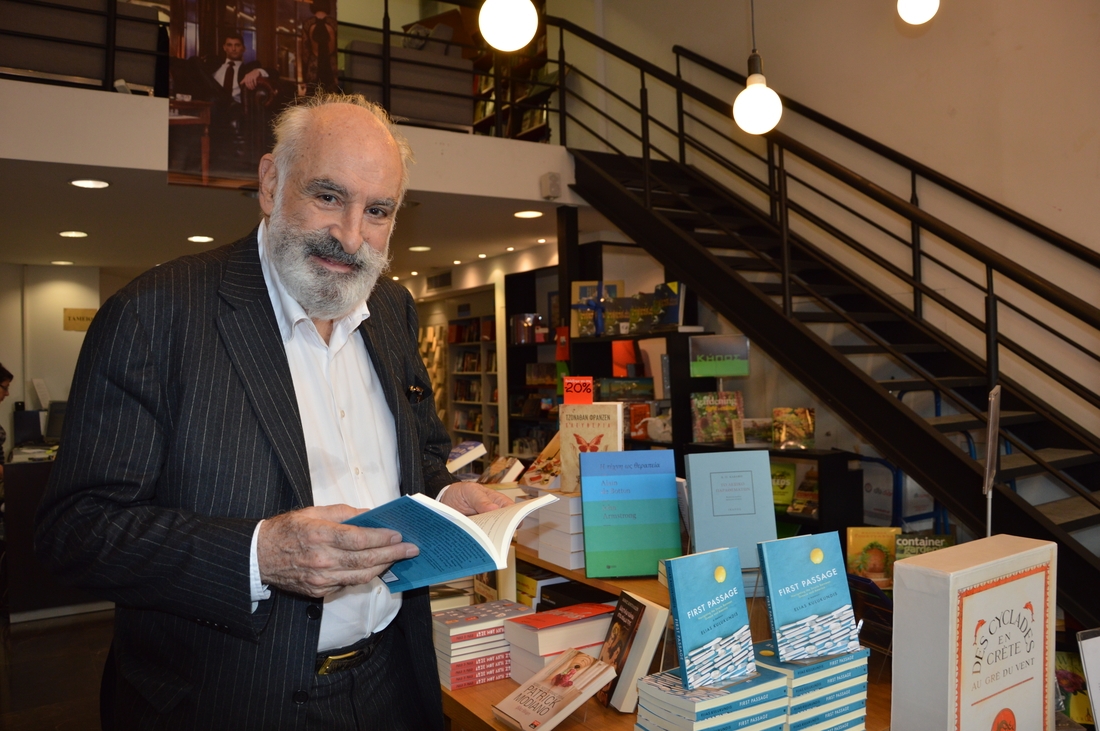

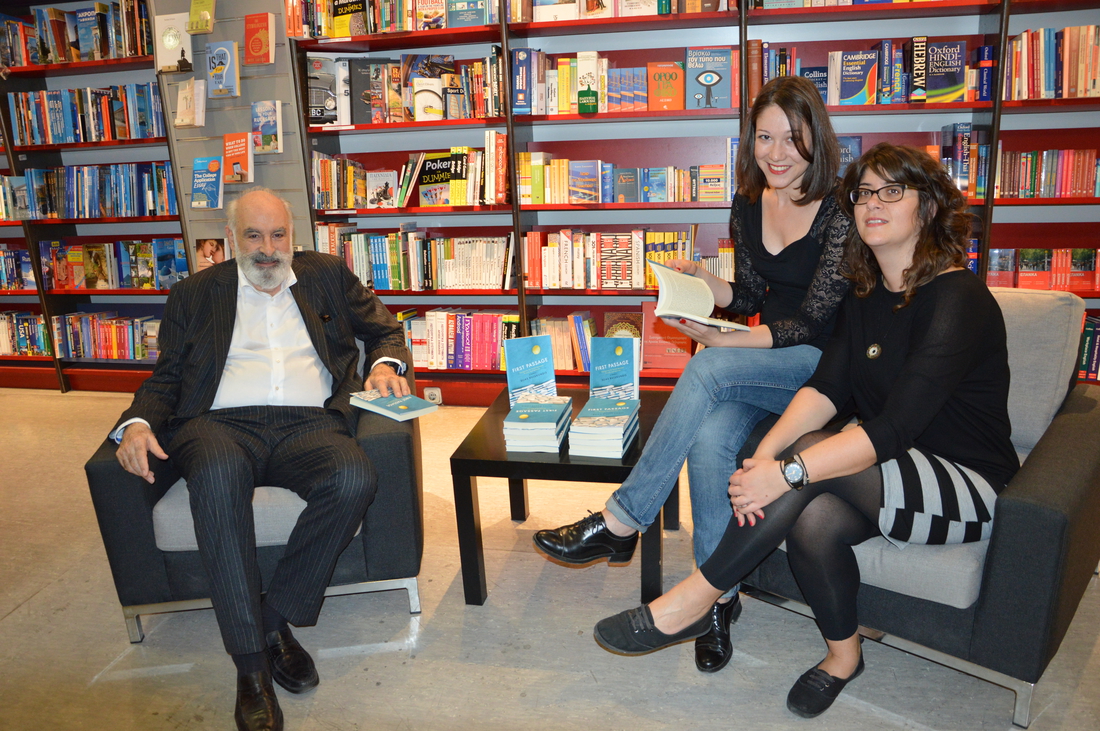

Grandson of two Kasiot sea captains, Elias Kulukundis was born in London in 1937. Three years later his family moved to America and he grew up in Rye, New York. Educated at Phillips Exeter and Harvard, he became a versatile linguist as well as a writer. As a multifarious personality, Elias has searched the most interesting aspects of being a human in the modern society. He has published three books so far, The Feasts of Memory and The Amorgos Conspiracy, that can be found in English and Greek through his website www.eliaskulukundis.com, and the translation of Viktor Nekrasov’s Both Sides of the Ocean from the Russian. His fourth book, First Passage, has just been published ― and having created documentaries about politics and history, Elias is considered one of the cultural ambassadors of Greece among the other countries. Living-Postcards met him in Athens and discussed with him about how it is to be a cosmopolitan Greek nowadays as well as what Greece looks like to other people around the world.

What’s the modern meaning of being a Greek of Diaspora?

The concept of Greek literature of the diaspora was originated by Professor Yiorgos Kalogeras of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, who in turn was inspired by my first book, The Feasts of Memory. Speaking at the Hellenic Centre in London in 2013, I took the concept a step further when I spoke of Greece Without Borders. In my opinion, despite the poor opinion of Ottoman rule held by Greeks in general, I believe that the Greek nation flourished as part of the Ottoman Empire in a way that it has not flourished since. Under the Ottomans, Greeks controlled much of the area’s trade. The Empire provided a ready market for Greek products, much as the European Union provides a market for German exports today. What Greeks lacked of course, and what they longed for was the Greek nation-state, which Greeks were willing to fight and die for from the time of the Greek revolution, throughout the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century. Ironically, that very nation-state, which Greeks once prized so highly, is now being dominated by another supra-national entity in the form of the Eurozone, the European Union and the entities allied with them (i.e. the International Monetary Fund. and the European Commission.

Nevertheless, in the concept of Greece Without Borders, Greece as an idea remains perfectly intact. A concept of Hellenism continues to bind together Greeks in Europe, the Americas, New Zealand and Australia and other parts of Asia and Africa in the way that the Greek nation was united in a cultural, commercial and moral sense as a “millet”, one of ethnic entities that flourished under Ottoman rule. Whatever else we do to improve our position, we must see ourselves again as that successful “nation”, a revived Greece “without borders.”

Would you describe yourself as Greek living abroad, or as a person that just has Greek roots that “haunt” him no matter where he lives?

For much of my life, I would say I was “haunted” by my Greek roots. Then I read something the French writer André Malraux said - “a heritage cannot be acquired. It must be conquered.” For me this process of conquest of my Greek roots was accomplished over time. The process began with my first book, The feasts of memory and it was subsequently carried on by the political project that became The Amorgos Conspiracy in reality, as well as the writing of book itself, so that now I think I can safely say that I feel myself in control of my Greek roots rather feeling haunted by them.

As for whether I feel I am a Greek who lives abroad, I prefer to say simply that I am a Greek who was raised abroad. My ancestry is from the Aegean island of Kasos. My grandparents moved to Syros where my parents were born, and as I live in Athens now, I feel like many of the Aegean islanders of the ancient times, who came from outlying areas but settled in the capital.

Your book “The Amorgos Conspiracy” deals with the Greek junta period 1967-74. It is a true story that represents the facts in a literature way. Would you say that history is meant to have different meanings? Is ideology or someone’s background above historical facts?

Unfortunately, ideology plays a big role in the interpretation of history. I say unfortunately because ideology colors the way humans perceive their history and inevitably distorts their understanding of it.

People in the United States generally view their history to be one long and consistent march to a better life for all its citizens, and aspects such as slavery and racial injustice tend to be glossed over as the exceptions rather than the norm. The ideology of capitalism as a success story continues to hold sway over American thinking, despite ever increasing evidence of capitalism’s manifest weaknesses. Even to say that, provokes an ideological reaction. “Who are you to say that capitalism has weaknesses? Some kind of communist?”

In The Amorgos Conspiracy, the question of ideology takes center stage. Left-wing thinking decided that a center-left politician could not have been rescued by the son of a ship-owner. That was an ideological impossibility, and faced with the incontrovertible historical fact that this ideological impossibility did actually happen, the facts of the matter had to be ignored or actually changed. Ideology is the villain of The Amorgos Consiracy, and the sway that ideology has over people’s minds. Ideology is a convenient way to avoid thinking, and unfortunately Greeks, as other people, are very often prone to take the easy way.

You are preparing your new book, a memoir about a young boy with Greek roots, living in the USA, growing up in a shipping family. Tell us a few things about what’s going on with the story in this memoir.

The boy I write about in my new book First Passage is not aware that he has Greek roots. He just knows that he is alive, and that many things happen to him that do not seem to make sense. His parents speak a different language from that of his schoolmates, a language which in fact was the first language the boy himself spoke until he arrived with his mother in New York harbor and his whole world was turned upside down. It will take the boy a lifetime to make sense of that confusion, to arrive at the point where he can become aware of his Greek roots and see them as something constant and lasting in his life. First Passage is the first installment of that story, the first chapter in what will in fact turn out to be a life-long struggle. I said about my first book that The Feasts of Memory was an “autobiography of everything that did not happen to me.” First Passage is an autobiography of many things that did happen.

As a cosmopolitan persona, what would you say about how Greece and the Greek actuality are depicted before other peoples’ eyes?

Greece has provided the world with ongoing inspiration, and with ongoing fantasy, often both. Many of the most interesting accounts of Greece have been written by non-Greeks, from the European adventurers who traveled the Greek lands in medieval times, to Lord Byron at the time of the Greek revolution, to more recent travellers like Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell and Shirley Valentine. The myth of Zorba the Greek rose to ascendancy in the 1960’s. Projected by two Greeks, though island Greeks, Nikos Kazantzakis the author who was Cretan and Michael Cacoyiannis the director of the film who was Cypriot, “Zorba the Greek,” put Greece on the map as a tourist destination. According to the picture conveyed by the film, Greeks are eccentric individualists, spontaneous and free. It would be up to Greeks in any large contemporary gathering, from a concert at Megaron Mousikis to a Sunday liturgy at any of Greece’s cathedrals, to judge how many Zorba’s there are to be found in a normal Greek gathering. And that is all right, as a people, we Greeks know the usefulness of myths.

You share your life among Berlin, Syros, Athens and New York City. Is there any difference of “Greekness” in those places for you?

Like the turtle I bring my “house” with me wherever I go. Sometimes, when I am deeply immersed in writing and “come up for air” for a moment, I have to look around to determine where in the world I am. In many ways, with the exception of Syros, the places I frequent are similar. Athens, New York and Berlin are all cultural capitals. Athens and New York have a similar pace of life, which is fast. Berlin is like New York in that it is not precisely Germany the way New York is not exactly America. In a way, both are nations in themselves. Viewing a place in that way, incidentally is a Greek idea—the idea of the nation-state was invented in Greece.

You are a published author of numerous articles about history, politics and Greece’s modern era. What’s the most interesting feedback you’ve gotten so far about your writings?

Last evening a woman I met at a gathering, who had read The Amorgos Conspiracy, referred to the fact that for a long time since the events originally took place, the story of the rescue was not known. The woman added that it was important for people to know the stories that make up their history, and thus the book had made a contribution. Putting the matter in that light was a revelation to me. It pointed up the relation of The Amorgos Conspiracy to the stories I recounted in The Feasts of Memory, and other stories we may want to retell, which make up our historical DNA. They are like photographs in an album, and it is the task of writing to preserve these photographs, arrange them in a way so that it is interesting to look at them, so that every so often when the spirit moves us, we can open the book.

Is there a “secret tip” you would like to tell people reading us here about the situation in Greece nowadays?

I would say that the recent negotiations with the Eurozone have shown us that although we are to some extent dependent on outside forces, those outside forces are also dependent on us. People like to say that Greece is the problem, but the real questions at stake have to do with Europe, and what kind of a continent we want Europe to be — what kind of a world we want to live in. In this respect, we Greeks can play a leadership role. Hardly anyone else is thinking about these questions. An American friend of mine told me recently, “in other places, the issue is not so clear. Economists can’t tell if the U.S. is really growing or not. But with Greece, there is no doubt. In Greece, it’s obvious — the system is not working. The question now is what do we do about it?”

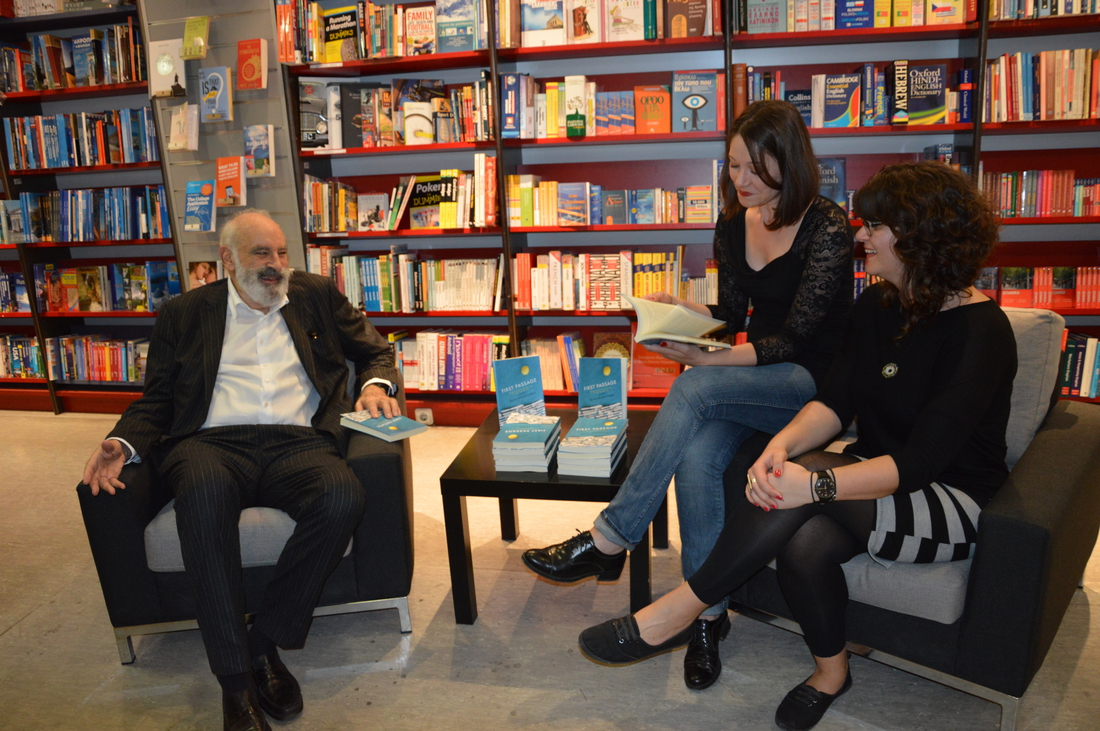

(We thank Medianeras for the concept, and Eleftheroudakis bookstore for hospitality)